In the 1850 census, a woman listed simply as Catharine Pinkham appears in a wealthy white household in Newtown. She was sixty-eight years old—born around 1782, during the Revolutionary War. The census gives us almost nothing else: no occupation, no property, just a name and an age. But that age tells a story the enumerator never intended to record. Catharine had lived through the birth of a nation that debated whether she was fully human, survived the gradual emancipation that freed New York’s enslaved only in 1827, and carried forward memories of a world that predated American independence. She was, in the language of Kwanzaa’s seventh principle, a keeper of Imani—faith—not merely as spiritual belief, but as the conviction that a community could endure.

Imani calls on a people to believe in their ancestors, their leaders, and the righteousness of their struggle. For Newtown’s free Black residents, this faith manifested not as abstraction but as measurable persistence—elders who linked generations to revolutionary memory, institutions that outlasted the pressures against them, families who appear decade after decade in census records, and sacred ground that preserved spiritual continuity when all else threatened to erase them.

Keepers of Revolutionary Memory

Scattered throughout Newtown’s census records are elderly residents whose birth years place them in the colonial era—people who had witnessed the transformation from British colony to slaveholding republic to a state that finally, belatedly, abolished bondage in 1827. These centenarians and near-centenarians were living archives, their memories reaching back to a time before the Constitution existed.

Some claimed ages that seem improbable—105, 110, even older. Census takers may have misheard or misrecorded. But another reading is possible: these extreme ages represented assertion rather than confusion, a demand for recognition of extraordinary endurance. To claim 110 years in 1850 was to claim birth in 1740, to insist on connection to a world before independence, to position oneself as a living bridge between eras. Whether literally accurate or strategically claimed, these ages announced that someone had survived what was not meant to be survived.

Peter Peterson, documented at sixty-two in the 1850 census, would have been born around 1788—just as the Constitution was being ratified, its infamous three-fifths clause reducing enslaved people to fractional humanity for purposes of political representation. He lived to see his surname spread across six separate households in Newtown, a network of at least thirty-two Petersons forming the largest documented extended family in the community. His generation transmitted not just names but strategies, not just memory but method.

Institutional Persistence

The churches that anchored Newtown’s Black community were themselves acts of faith in the face of hostility. The United African Society of Newtown, founded in 1828—just one year after emancipation—demonstrated a community unwilling to wait for recognition. They built institutions immediately, refusing to let the fragility of their legal status delay the work of self-organization.

These congregations operated under constant pressure. The AME Zion and Baptist churches that served Black New Yorkers had emerged from explicit rejection—congregants who had been relegated to segregated galleries or made to wait for communion until whites had finished. Mother AME Zion Church in New York City, described by its current pastor as “the grand depot of the Underground Railroad,” traced its origins to 1796, when Black members left the white-controlled John Street Methodist Church to form their own congregation. The pattern repeated across the region: exclusion met with institution-building, rejection answered with sacred spaces claimed on Black terms.

The presence of abolitionists like James W.C. Pennington and Samuel Ringgold Ward in the Newtown area connected local congregations to broader networks of resistance. These churches were not merely spiritual refuges; they were nodes in an infrastructure of freedom, spaces where literacy was taught, where mutual aid was organized, where the work of liberation was planned and sustained across decades.

Families Across Censuses

The census records reveal something remarkable: families who stayed. In a world that offered every incentive to scatter—economic precarity, legal vulnerability, the constant threat that slavery’s reach might extend north—Newtown’s free Black families appear decade after decade, their surnames persisting, their household networks expanding.

The Peterson network exemplifies this staying power. Six households across the 1850 census, spanning multiple generations, holding property, maintaining occupational diversity. John Peterson Sr. at sixty-five headed a household of twelve, including adult children in their twenties who remained rather than striking out alone. This was not economic failure but family strategy—pooled labor, shared resources, collective resilience against individual vulnerability. Four working-age men contributing wages to a single household economy created security that solitary workers could never achieve.

Tracing families from 1830 through 1860 reveals patterns of accumulation and investment. The 1830 census recorded 483 free Black individuals but no property data. By 1850, property values appear in the record, and gardener households show holdings from $250 to over $1,000—substantial wealth in an era when property ownership conferred not just economic security but civic standing. By 1860, these patterns had deepened. Families that had been propertyless in 1850 now owned real estate. Children who had appeared as minors now headed their own households nearby. The geographic clustering was deliberate: proximity enabled mutual support, shared labor, collective protection.

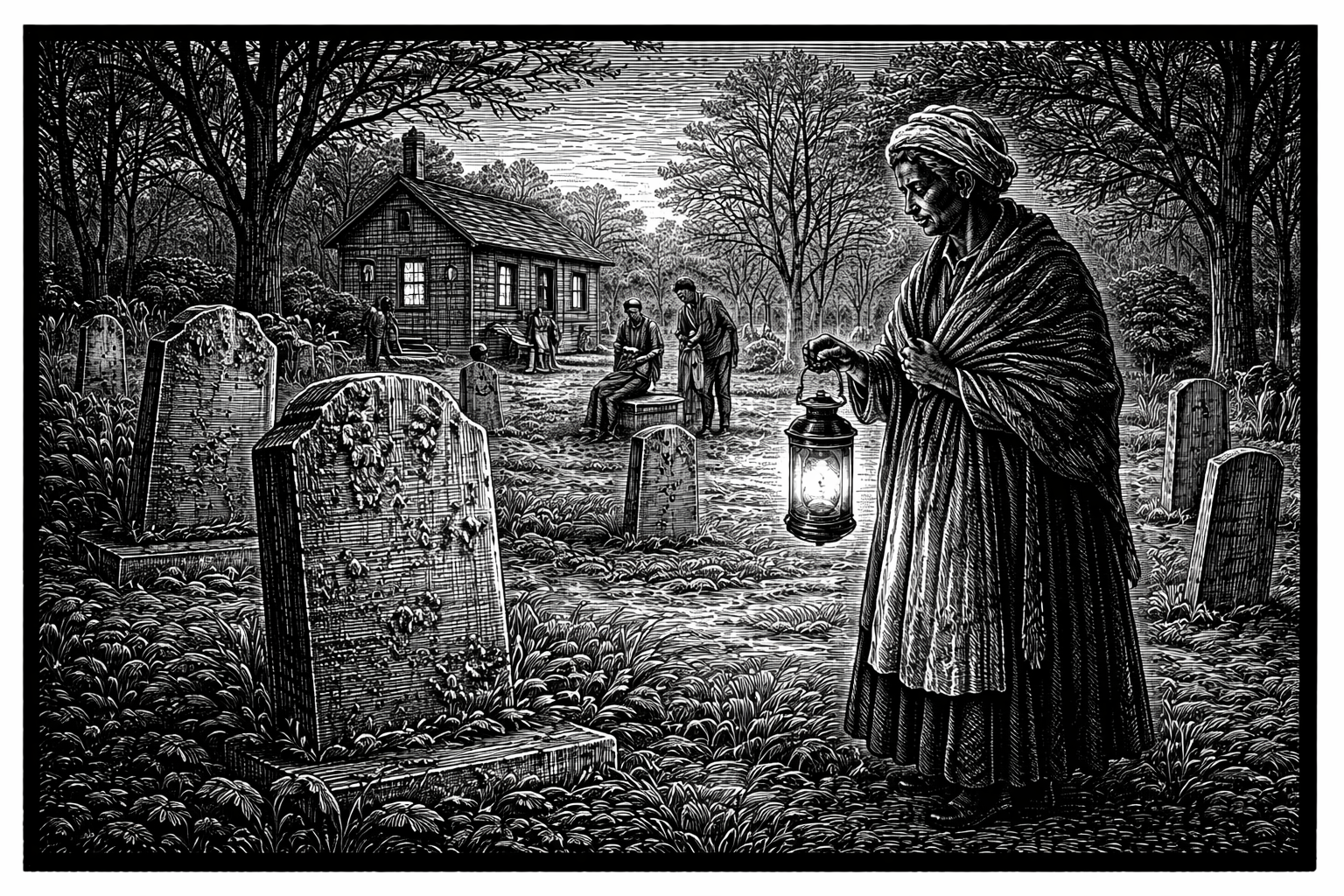

Sacred Ground as Spiritual Continuity

Perhaps nowhere is Imani more literally grounded than in the burial sites where Newtown’s free Black residents laid their dead to rest. The African burial ground at 47-11 90th Street in what is now Elmhurst has survived nearly three centuries—a fragment of sacred space that predates almost everything else in the neighborhood. Founded in 1828, the same year as the United African Society of Newtown, it represented the community’s insistence on honoring their dead according to their own traditions, in ground they claimed as their own.

Burial grounds were among the first institutions African Americans established wherever they formed communities. The African Burial Ground in lower Manhattan, used from the late 1690s until 1794, held an estimated 15,000 people before being paved over and forgotten. Its rediscovery in 1991 during construction of a federal building sparked a community-led movement that ultimately resulted in a National Monument—proof that sacred ground, once remembered, demands recognition.

The Elmhurst burial ground faces similar pressures. Development threatens what community advocates have worked to protect. The Elmhurst History and Cemeteries Preservation Society has submitted requests for landmark status, arguing that this tiny surviving fragment deserves the same recognition given to Dutch colonial cemeteries in the area. The cemetery at Flatbush, another African burial ground recently transferred to New York City Parks, demonstrates that advocacy can succeed—but only when communities organize and persist.

These burial grounds matter because they represent continuity beyond individual lifespans. The bodies interred there connected the living to their ancestors, the present to the past. To bury one’s dead in ground one claimed was to assert that this community belonged here, had history here, would endure here. When everything else could be taken—property seized, families separated, legal status revoked—the dead remained where they had been placed, a permanent claim on the land.

Faith as Methodology

Viewed through the lens of Kwanzaa, Imani illuminates what the census could never capture: the faith that made persistence possible. Census records count bodies, measure property, categorize by race. They cannot measure conviction. They cannot record the decision, made again and again across decades, to stay when leaving might have been easier, to build when destruction seemed inevitable, to document when erasure was official policy.

The centenarians who carried revolutionary memory, the churches that persisted across generations, the families that appear and reappear in census after census, the burial grounds that hold their dead—all represent faith enacted. Not faith as passive hope, but faith as daily practice, as institutional commitment, as the stubborn insistence on a future that might or might not arrive but that deserved preparation regardless.

In lighting the candle for Imani, we honor those who believed their community worth preserving even when the republic that claimed them refused to acknowledge their full humanity. Their continuity was not passive survival but active resistance—a faith made tangible through institutions, through family networks, through sacred ground that still holds the bones of their ancestors. They did not merely endure. They built. And what they built endures still, waiting to be remembered.

[Based on analysis of Federal Census records, 1830-1860, Newtown Township, Queens County, New York, documenting persistence and continuity in Free Black communities.]

Leave a Reply