Hunger data usually arrives dressed up as a percentage—clean, bloodless, easy to skim. The more honest version is a headcount: how many people have crossed into “Crisis or worse” hunger (IPC Phase 3+), the zone where a household can’t meet basic food needs without dismantling its own future—selling tools, skipping meals, pulling kids from school, trading tomorrow for today.

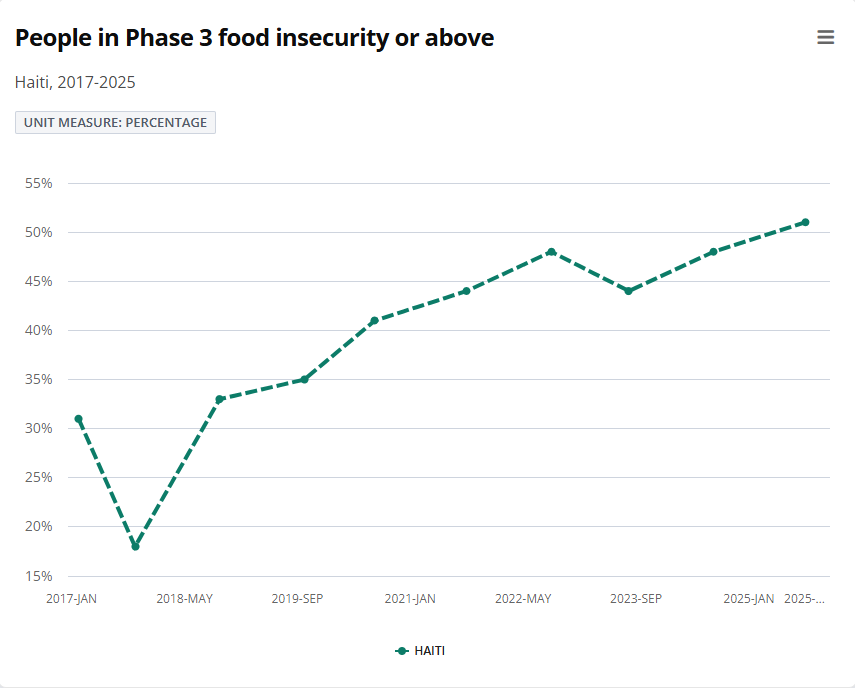

Haiti is the clearest case study in what these numbers really mean. A Reuters report citing the latest IPC analysis projects that by mid-2026 nearly 6 million Haitians—more than half the country—could face severe food insecurity. Right now, the estimate is about 5.7 million, and roughly 1.9 million are already in “Emergency” conditions—acute shortages and high malnutrition risk. The IPC has not declared famine, but the warning is blunt: the trajectory is worsening, and any gains are fragile.

The drivers aren’t mysterious—they’re modern. Six years of economic contraction plus expanding gang violence turns food into a logistics problem and then into a political weapon. Displacement breaks local farming cycles; blocked roads and shuttered businesses break markets; fear breaks the ordinary routines that keep calories moving from field to table.

Zoom out and the implication is bigger than Haiti: IPC Phase 3+ is a stress test for state capacity. When the count stays high month after month, it signals something more durable than a “shock.” It’s a system that can’t reset. And once crisis becomes baseline, everything else gets more expensive—healthcare, schooling, security, migration, and eventually recovery itself.

Aid groups are increasingly explicit about what this kind of data demands: not just emergency food, but long-term investment in stability and livelihoods—because you can’t “airdrop” your way out of a collapsed food economy.

Leave a Reply