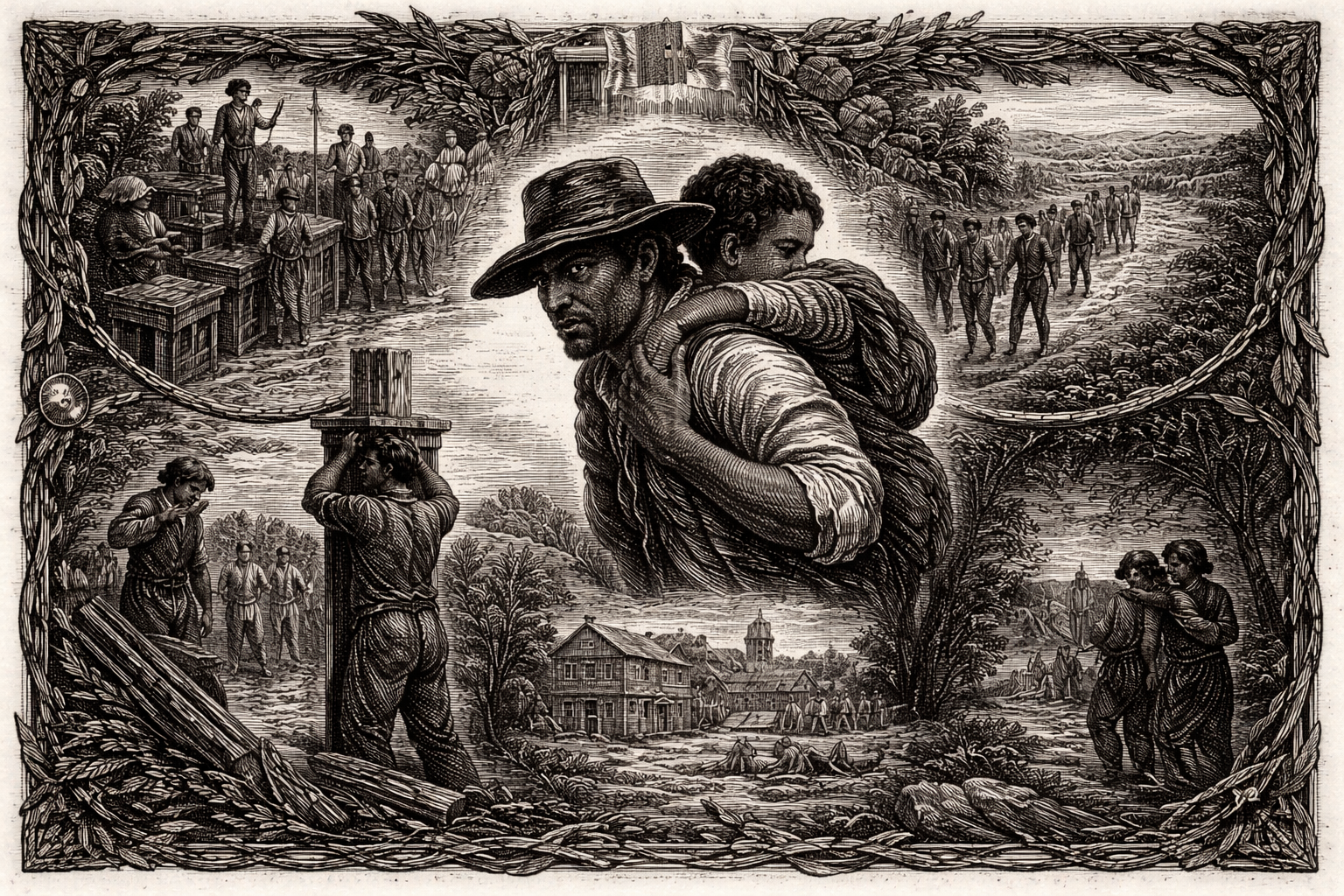

Josiah Henson was born on June 15, 1789, in Charles County, Maryland, on a tobacco plantation in Port Tobacco where his family endured the systematic brutalities that defined American slavery.¹ His earliest memories were seared with violence: when his father defended Josiah’s mother from an overseer’s assault, he received one hundred lashes, had his right ear nailed to a whipping post before being severed, and was subsequently sold to a slaveholder in Alabama—never to be seen again by his family.² This paternal resistance and its savage consequences would shape Henson’s understanding of slavery’s fundamental injustice, even as he initially sought accommodation within its confines.

When Henson was five or six years old, the death of his enslaver triggered an estate sale that scattered his family across Maryland’s slave markets.³ Purchased separately at auction, the terrified child fell desperately ill under his new owner’s neglect. Only his mother’s tearful plea convinced Isaac Riley of Montgomery County to acquire the seemingly worthless boy for “a trifling sum.”⁴ Her intervention saved his life. Reunited with his mother on Riley’s farm, Henson recovered and grew into a physically powerful young man whose intelligence and work ethic earned him the rare position of farm superintendent while still in his early twenties.

Riley’s farm operated on the characteristic dynamics of paternalistic slavery. The frequently drunk and financially reckless master increasingly depended on Henson’s management capabilities, allowing him unusual autonomy to conduct business, travel, and even preach at Methodist churches.⁵ Henson leveraged this trust to improve conditions for the enslaved community under his supervision, negotiating additional food rations and modest comforts. Yet this privileged position came at a moral cost that would soon test his understanding of freedom itself.

In 1825, financial difficulties forced Riley to transfer eighteen enslaved people—including Henson’s wife Charlotte and their children—to his brother Amos Riley’s Kentucky plantation.⁶ Riley extracted a binding promise from Henson to deliver this human property safely across state lines. The route passed directly through Ohio, where free soil beckoned and other Black residents urged the entire group to remain. But Henson, believing that honorable conduct and continued service would eventually secure legitimate manumission, refused to break his oath. He delivered every person, including his own family, into continued bondage in Kentucky.⁷

The shattering of this faith began three years later. In 1828, encouraged by an abolitionist-minded white Methodist minister, Henson requested permission to negotiate his freedom directly with Isaac Riley.⁸ On the journey back to Maryland, Henson preached at churches and camp meetings, raising $275 in donations. Riley, whose farm had badly deteriorated in the intervening years, agreed to sell Henson’s freedom for $450. Henson paid $350 immediately—his life savings plus proceeds from selling his horse—with the remaining $100 to be earned through continued labor.⁹

The betrayal was methodical and complete. Riley promised to forward proper manumission papers to Kentucky but instead sent letters claiming the agreed price was actually $1,000.¹⁰ When Henson returned to discover this deception, his fury gave way to devastating clarity: under slavery’s legal architecture, even exemplary service guaranteed nothing, because the law recognized him as property rather than person. Worse still, the Riley brothers subsequently conspired to sell Henson to the Deep South, where he would be permanently separated from his family.¹¹

In September 1830, facing this final betrayal, Henson chose self-emancipation.¹² He fled Kentucky at night with Charlotte and their four children, traveling on foot through Indiana and Ohio, often carrying the youngest children on his back while hiding in forests by day. On October 28, 1830, after six weeks of dangerous travel, they crossed into Upper Canada near Fort Erie, where British law placed them beyond slavery’s reach.¹³

In Canada, Henson transformed from fugitive to founder. By 1838, he had emerged as a leader among the growing community of freedom seekers, establishing the Dawn Settlement near Dresden in Ontario’s Kent County.¹⁴ At its core stood the British American Institute, opened in 1842 as one of Canada’s first vocational schools, where former slaves learned trades including carpentry, blacksmithing, and industrial skills.¹⁵ The settlement cultivated wheat, corn, and tobacco, and exported black walnut lumber to American and British markets. At its height, Dawn housed approximately 500 residents building lives based on collective self-sufficiency and mutual aid.¹⁶

To raise funds for the settlement, Henson published his autobiography in 1849 under the title The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself.¹⁷ The narrative detailed his experiences with such searing honesty that Harriet Beecher Stowe later cited Henson’s account among her sources for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, published in 1852.¹⁸ Though the association with Stowe’s character became both famous and controversial, Henson’s actual life bore little resemblance to the passive suffering of literary “Uncle Tom.” He served as captain of a Black militia unit during the 1837 Canadian Rebellion, made multiple dangerous trips back into slave states to guide over 100 people to freedom via the Underground Railroad, and met with Queen Victoria during fundraising tours of Britain.¹⁹

Henson continued preaching at Dresden’s British Methodist Episcopal Church until his death on May 5, 1883, at age ninety-three.²⁰ His life demonstrated that freedom was never a reward bestowed by benevolent masters, but a fundamental right that enslaved people claimed through courage, collective action, and uncompromising determination to define their own humanity beyond slavery’s legal fictions. The Dawn Settlement’s success proved that given land, education, and autonomy, formerly enslaved people could build thriving communities that challenged every racist assumption undergirding slavery itself.

Endnotes:

- Josiah Henson, The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada, as Narrated by Himself (Boston: Arthur D. Phelps, 1849), 1-3.

- Henson, Life, 3-4; “Josiah Henson,” Maryland State Archives, MSA SC 5496-8783.

- Henson, Life, 5.

- Henson, Life, 5-6.

- Henson, Life, 8-10.

- Henson, Life, 20-23; “Josiah Henson,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, accessed February 2026.

- Henson, Life, 23.

- Henson, Life, 28-30.

- “Josiah Henson,” Maryland State Archives; Henson, Life, 30-31.

- Henson, Life, 32-33.

- Henson, Life, 35-37; “Josiah Henson,” National Park Service, accessed February 2026.

- Henson, Life, 39-41.

- Henson, Life, 42-44; “Josiah Henson,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, accessed February 2026.

- Ontario Heritage Trust, “Josiah Henson Museum of African-Canadian History: History,” accessed February 2026.

- Ontario Heritage Trust; Encyclopedia Britannica, s.v. “Josiah Henson,” last modified April 29, 2014.

- Robin W. Winks, The Blacks in Canada: A History, 2nd ed. (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1997), 168-170.

- Henson, Life, title page.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1853), 26-27.

- Ontario Heritage Trust; Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, journal entry, June 26, 1846, cited in “Josiah Henson,” National Park Service.

- Ontario Heritage Trust.

Leave a Reply