In the bustling commercial heart of 19th-century New York City, oysters were everywhere. They were cheap, abundant, and consumed by all classes. Yet within this seemingly ordinary food economy, one man quietly transformed hospitality into an engine of resistance. Thomas Downing, a free Black entrepreneur born in Virginia in 1791, built one of the most famous restaurants in antebellum Manhattan—while simultaneously turning its subterranean spaces into sites of abolitionist action.

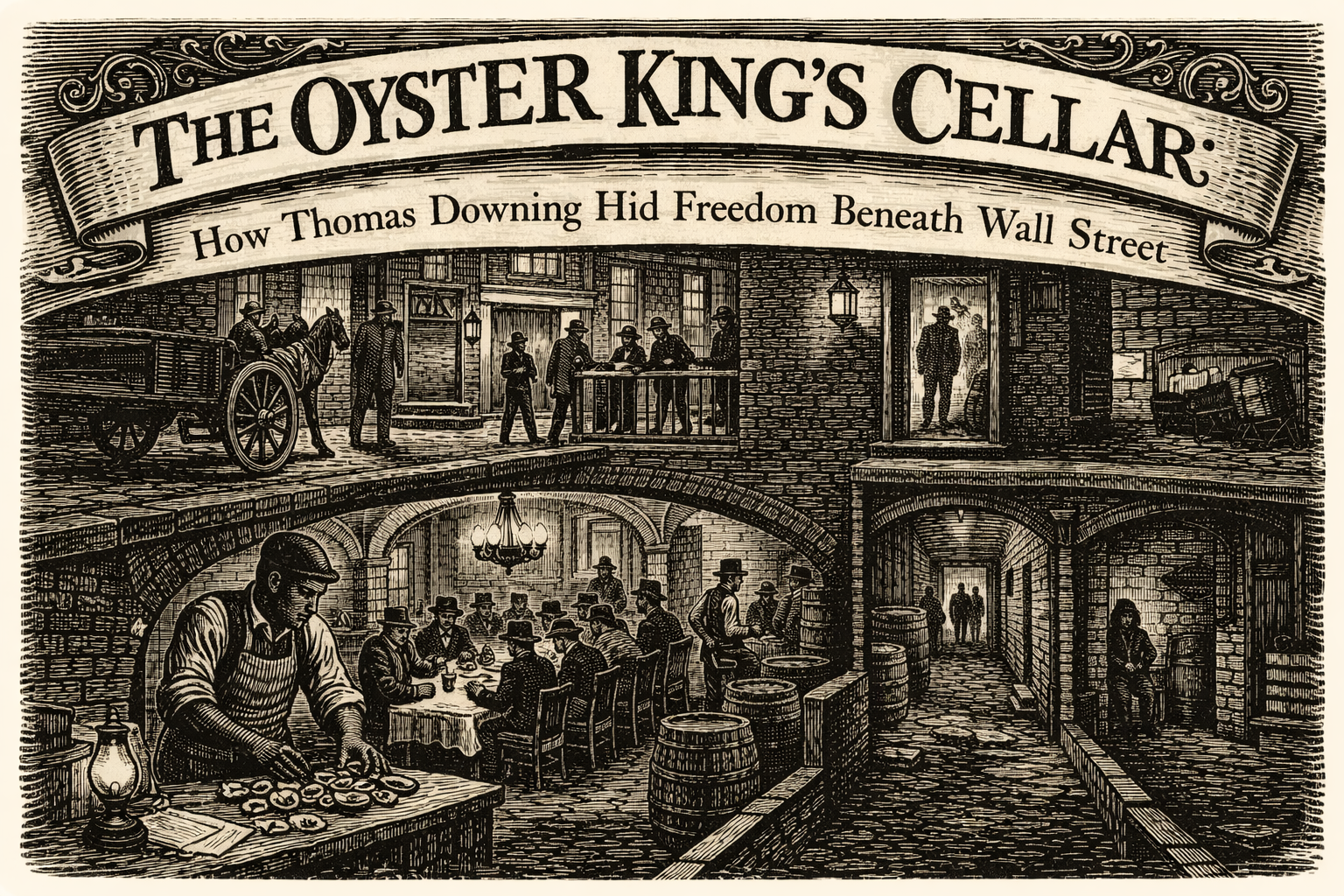

Downing arrived in New York in 1819 already steeped in the oyster trade. Raised on Chincoteague Island, his early life revolved around fishing, raking oysters, and maritime labor. By the mid-1820s, he had opened an oyster “refectory” in the basement of a building near Broad and Wall Streets. Like many oyster houses of the era, Downing’s establishment sat partially below street level, accessed by stairs descending into a cool cellar. What distinguished his operation, however, was refinement. Contemporary observers described mirrored arcades, fine carpets, chandeliers, and a level of comfort unmatched by the rougher oyster cellars of the Bowery or Canal Street. Downing’s clientele included bankers, politicians, newspaper editors, visiting dignitaries, and European travelers—members of New York’s white elite who made his restaurant a downtown institution.

Yet beneath this polished surface lay a different story. The physical layout that made oyster houses efficient—cellars for storage, vaults for keeping shellfish alive, back corridors for staff and deliveries—also made them ideal spaces for concealment. According to family accounts and later historical reconstructions, Downing used these basements to shelter freedom seekers moving through New York as part of the Underground Railroad. Enslaved people on the run could be hidden among oyster barrels and storage rooms, protected by trusted Black staff and the constant churn of commercial activity. In a city where kidnapping of free Black people remained a real threat even after New York’s gradual abolition of slavery, discretion was essential.

Downing’s abolitionist commitments extended well beyond covert sheltering. In 1836, he helped found the United Anti-Slavery Society of the City of New York, an all-Black organization formed in response to the limitations of white-led abolitionist groups. He served on its executive committee and remained active as the organization merged into broader citywide anti-slavery efforts. After the formal end of slavery in New York State in 1837, Downing also became a leading figure in the Committee of Thirteen, which worked to protect free Black residents from being kidnapped and sold into Southern slavery—a practice that would later gain national attention through the story of Solomon Northup.

Education was another pillar of Downing’s activism. Alongside other Black leaders, he challenged the administration of New York’s African Free Schools, protesting the lack of Black teachers and the paternalistic oversight of white managers aligned with colonization schemes. These efforts contributed to structural changes within the school system and reinforced a broader demand for Black self-determination in civic life.

What makes Downing particularly significant is not only his prominence, but what his life reveals about how freedom was engineered in urban environments. The Underground Railroad did not function solely through rural safe houses or isolated barns. It also relied on businesses, kitchens, and cellars embedded in the commercial fabric of cities. Oyster houses, staffed largely by free Black men and operating at all hours, provided cover, mobility, and access to resources. They were places where white scrutiny was blunted by familiarity and appetite.

Downing’s success also mattered. His social capital—earned through decades of impeccable service to New York’s elite—gave him a degree of protection unavailable to most Black New Yorkers. When disputes arose, his patrons often stood behind him. When he died in 1866, the New York Chamber of Commerce reportedly closed in his honor, a rare acknowledgment for a Black man in the era.

Thomas Downing reminds us that resistance often hides in plain sight. In the basements of oyster houses, amid the smell of brine and the clatter of plates, freedom moved quietly through the city. Hospitality became infrastructure. Commerce became cover. And beneath Manhattan’s streets, the architecture of everyday life was repurposed in service of liberation.

Endnotes

- John H. Hewitt, “Mr. Downing and His Oyster House: The Life and Good Works of an African-American Entrepreneur,” New York History, Vol. 74, No. 3 (1993).

- George T. Downing, “A Sketch of the Life and Times of Thomas Downing,” A.M.E. Church Review (1887).

- Francis Lam, “How Thomas Downing Became the Black Oyster King of New York,” The Splendid Table (2018).

- Sarah Richardson, Those Indomitable Downings, American History magazine (2022).

- Shane White, Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770–1810 (University of Georgia Press, 1991).

- Purvis M. Carter, “The Negro in Periodical Literature,” Journal of Negro History (1997).

Leave a Reply