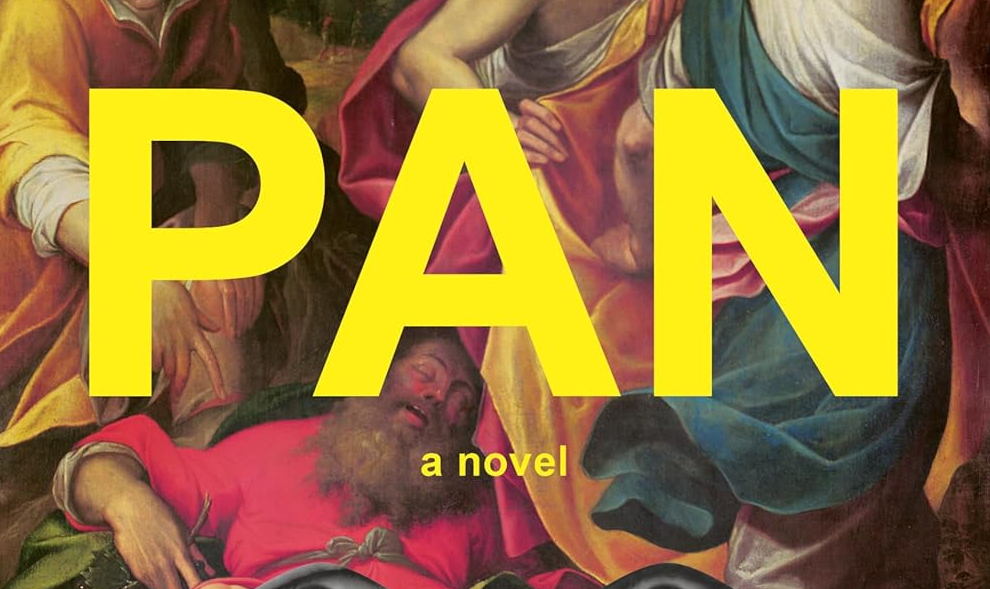

There are novels that peer into the mind. Then there are novels that live there—twitching, mutating, electrocuted with perception. Michael Clune’s debut Pan does the latter, with the devotion of a mystic and the relish of a heretic.

It is a book that doesn’t simply render adolescence as a phase, a corridor, a hormone storm; it renders it as a metaphysical condition, a permanent thought experiment. This is not Holden Caulfield’s world. This is Ivanhoe read at 4:30 a.m. to stave off cardiac arrest, this is Bach described as “math class for feelings,” this is spring sunlight that doesn’t fall on bricks, but into them.

Nicholas, 15, suburban, unmoored, is our daemon-guide. He lives with his father in the outer rings of Chicago and drifts through Catholic school like a visitor from another frequency.

Diagnosed with a panic disorder, he’s told to breathe into a paper bag. He complies—with zero conviction and maximum irony. These “medical bags” become props in his daily theatre of dread, producing hilariously surreal encounters (a nun suspects he’s using them to steal things). But that’s just the surface. Beneath it churns a teenage consciousness so exquisitely sensitive, so porous to myth and metaphor, that panic begins to feel like prophecy.

Clune, a memoirist of searing intelligence (White Out, Gamelife), writes with the precision of a physicist and the abandon of a junkie philosopher. Pan is not a novel of events but of episodes, not arcs but orbits. Nicholas and his best friend Ty fall under the spell of Tod—a kid so epically cool he might as well have been carved from denim. In Tod’s barn, they smoke weed, trade low-grade metaphysics (“Do you want to know the secret of how to get solid mind?”), and enter a kind of Dionysian puberty cult led by Tod’s older brother Ian.

What begins as teen rebellion turns into something stranger, ritualistic, almost religious. It’s here that Clune invokes his titular god—not with sandals and flutes but as a whispering force of mind-melting dread. Pan doesn’t appear, he possesses.

This isn’t a metaphor for mental illness. This is the experience of it: volatile, hallucinatory, yet rich with clarity.

That’s the trick of the novel, and its genius. Nicholas’s panic attacks, which begin as textbook adolescent anxiety, transmute into something mythic. The story he tells himself—the Greek god is punishing him—becomes a viable reality inside the deranged logic of his internal weather system.

This isn’t a metaphor for mental illness. This is the experience of it: volatile, hallucinatory, yet rich with clarity. There are moments when Nicholas’s voice veers into high-register literary rapture, and yes, occasionally the seams show (“Wait a minute, that’s not Nicholas—that’s Clune”). But the rapture is worth it. Nicholas’s consciousness is a whirlpool of Wilde, Baudelaire, Camus, and Boston’s More Than a Feeling. He’s a stoner savant one moment, a metaphysical poet the next.

RELATED POST

Neuroplasticity and the Bildungsroman: Brain Development in Coming-of-Age Stories

The Bildungsroman reflects adolescent neuroplasticity, showcasing personal growth and transformation through experiences that shape identity and development. (READ MORE)

Clune’s gift is his ability to make this voice feel not only believable, but inevitable. He doesn’t condescend to teenage intensity, he dignifies it. There’s no “puppy love” here, no “it’s just a phase.” Nicholas experiences everything—friendship, art, terror, Sarah—with a skinless urgency. It is his now, his only now.

The novel’s empathy doesn’t stem from exposition but from texture: the angle of sunlight, the warp of time under the influence, the psychic topography of a face glimpsed too long. “The afternoon wore ‘Gilligan’s Island’ colors,” Nicholas observes, “like ’60s television, bleeding out a little over the edges of shapes. Like dead people remembering earth.” That line alone is worth the cover price.

Though comparisons have been made—to Proust, to Sebald, to Jenny Offill—Clune’s voice is weirder and funnier, and his form looser. He’s not trying to build a perfect machine of plot. He’s trying to record the audio from inside a malfunctioning brain.

If there is a flaw, it’s built into the book’s conceit: the line between narrator and author occasionally frays.

The structure is that of a consciousness fluttering between revelation and collapse, lit by sudden flashes of brilliance and blackout. There’s a memorable biofeedback scene with a therapist that borders on spiritual possession. There’s a moment when Nicholas finishes Ivanhoe, puts the book down, and promptly descends into panic. Narrative events here are never climaxes—they’re minor earthquakes in a field of neural tremors.

If there is a flaw, it’s built into the book’s conceit: the line between narrator and author occasionally frays. But even those frays offer something rare—a glimpse at the adult Clune leaning gently into the chaos of his younger self. The book is written in the past tense, but acknowledges that the past is always being viewed from some impossible angle—“coming from the future,” Nicholas says. That self-awareness doesn’t dilute the immediacy; it sharpens it.

Pan is, above all, a novel about how we feel things before we understand them. A bildungsroman where the coming-of-age is less a destination than a series of neurochemical eruptions. It doesn’t ask you to sympathize with Nicholas. It dares you to become him—to see like him, fear like him, love like him. And in doing so, it offers a rare gift: the reminder that our strangest, most private thoughts may be the most real parts of us.

WORDS: brice.

Leave a Reply